Hailing from central African cities of Brazzaville and Kinshasa, sapeurs have become increasingly recognizable around the world. Since the 1970s, sapeurs (from: le sape, short for “Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes”) have been known for donning technicolored three-piece suits with flamboyant accessories like golden walking sticks and leopard-print fedoras, and then cat-walking through their city streets.

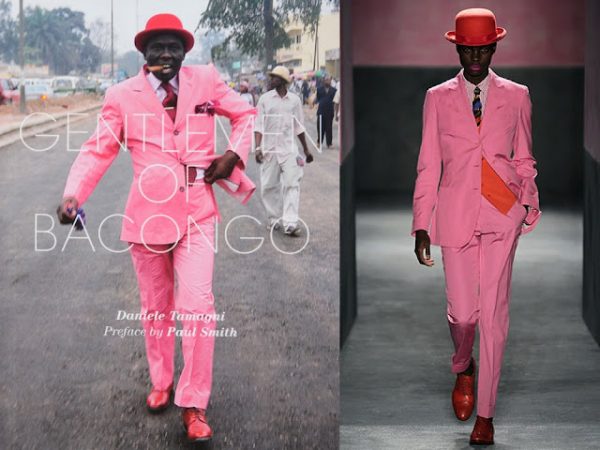

In recent years, Solange, Kendrick and SZA have all featured sapeurs in their music videos. The iconic British menswear designer Paul Smith did a whole spring line of sapeur-inspired suits and bowler hats.

If you want to be delighted, do a real quick image search. When you see the sapeurs, it’s obvious what makes them so attractive to famous artists and global brands. Their remix on classic menswear is irreverent and colorful and just a joy to look at.

These images are really different from the stereotypical way that sub-Saharan Africa is often portrayed to the world — depicted as broke and broken. As an American journalist who’s worked here for the past decade, I’ve seen those stereotypes. We all have. And, the reality is, life in places like the Congo is really difficult – especially after centuries of brutal colonization, resource extraction, and underdevelopment. Into that bleak frame strolls the sapeurs, these Congolese mechanics and construction workers and farm hands dressed up like aristocratic peacocks, flaunting their Ferragamo monk strap shoes, silk Chanel scarfs and crisp Versace suits.

Influences of this contemporary style can be traced back to Belgian colonizers — the Congolese found that it helped to look the part of the oppressor, fancy clothes and all. Modern sapeurs have likewise flipped the colonizer script in dramatic fashion. They continue to take the European suit — this thing that was forced on them — and make it wholly, authentically Congolese. And they’ve done it so well that now it’s the rest of us trying to wear our clothes to look like them.

Influences of this contemporary style can be traced back to Belgian colonizers — the Congolese found that it helped to look the part of the oppressor, fancy clothes and all. Modern sapeurs have likewise flipped the colonizer script in dramatic fashion. They continue to take the European suit — this thing that was forced on them — and make it wholly, authentically Congolese. And they’ve done it so well that now it’s the rest of us trying to wear our clothes to look like them.

By the 1980s, the Sapeurs had totally rebranded European formalwear. The Belgians had required Africans to wear suits to prove their European-ness; ut American jazz artists — at least, in the eyes of the Congolese — had worn suits to affirm their dignity.

Sapeurs believed that if you could find a way to dress expensively, the world would treat you like an expensive person – whether you were a famous rumba musician or a construction worker. To the sapeurs, fine formal wear announced to the world that you were the kind of person who deserved luxury. In the grand scheme, suits are a small thing. But La Sape formed as proof that anyone could be a person who mattered, just by looking the part. For a lot of young Congolese, that idea was extraordinary. So extraordinary that it didn’t matter that you were going to have to totally break the bank to make it happen.

By the early 2000s, Sapeurs were getting attention around the world. At the same time, journalists and photographers started traveling to Africa, to report on sapeur culture in Kinshasa and Brazzaville.

Last year, Congo hosted the Francophone Games – a kind of Olympics for the French-speaking world. The opening ceremony in Kinshasa was a medley of traditional Congolese dance, song, and puppetry. And then, in the middle of the show, the stadium suddenly went completely black. A row of yellow taxis appeared out of the darkness, headlights blazing. Then the doors flung open. A bunch of people in pinstripe suits and foot-tall top hats and iridescent gold blazers started pouring out.

They had gone mainstream – in the best possible way. This bold, extravagant cult of luxury fashion used to be counter culture. But when I was in Kinshasa, many Congolese told me that now, “la sape, c’est notre patrimoine national” – “la sape is our national heritage.”