In his 1936 autobiography, the composer Igor Stravinsky describes his 1912 visit to Bayreuth, Germany, to attend a performance of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal.

The opera tells the story of a quest for the Holy Grail by one of King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table, and draws upon a thirteenth-century Middle High German romance by knight and poet Wolfram von Eschenbach. Wagner freely mixes elements of the medieval work with his own idiosyncratic philosophical and anti-Semitic ideologies in his final opera, completed eight years after Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods”), the concluding part of his cycle of operas based on Norse mythology and German legend.

|

| Richard Wagner as Wotan (Odin) in an 1876 cartoon |

At the time of his trip to Germany, Stravinsky himself was in the midst of composing music for Le Sacre du printemps (“The Rite of Spring”), a ballet subtitled “Pictures of Pagan Russia.” In his autobiography, he describes the genesis of the piece:

I had a fleeting vision which came to me as a complete surprise, my mind at the moment being full of other things. I saw in my imagination a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring. Such was the theme of the Sacre du printemps.

Although both the German Wagner and the Russian Stravinsky turned to pagan subjects for inspiration, their music and worldviews were greatly at odds.

Religious mindset

For Stravinsky, religious subject matter was subsumed into a powerfully modernist artistic vision. He had a visceral reaction to witnessing the performance at Bayreuth, where Wagner – with the financial support of devoted donors and Bavarian King Ludwig II – had built an opera house in which only his own works were performed.

Stravinsky explains his reaction to the scene:

What I find revolting in the whole affair is the underlying conception which dictated it – the principle of putting a work of art on the same level as the sacred and symbolic ritual which constitutes a religious service. And, indeed, is not all this comedy of Bayreuth, with its ridiculous formalities, simply an unconscious aping of a religious rite?

It is not merely the showy theatricality of the Bayreuth production that disgusts Stravinsky; he is repulsed by the audience’s willing desire to be swept away in quasi-religious fervor.

After calling for the end of “this unseemly and sacrilegious conception of art as religion and the theatre as a temple,” Stravinsky forwards an argument against this conflation of attitudes.

[O]ne cannot imagine a believer adopting a critical attitude towards a religious service. That would be a contradiction in terms; the believer would cease to be a believer. The attitude of an audience is exactly the opposite. It is not dependent upon faith or blind submission. At a performance one admires or one rejects. One accepts only after having passed judgment, however little one may be aware of it. The critical faculty plays an essential part. To confound these two distinct lines of thought is to give proof of a complete lack of discernment, and certainly of bad taste.

This is, of course, a generalization about the religious mindset that takes the fundamentalist and literalist as synecdoche for the diverse world of approaches to religious belief and practice. This same process leads liberal American commenters to criticize “religious people” when they often actually mean “conservative evangelical Christians of rural America.”

But Stravinsky’s point stands regarding the suspension of critical faculties by the devotee of the artist. After all, the word fan is an abbreviation of fanatic. Whether the fan is a Wagnerite, a Tolkienite, or a #ReleaseTheSnyderCuttite, the move from appreciation to devotion often leads to both dissolution of discernment and hostility towards those who dare to discuss the object of affection on its merits.

Like the sacrificer in the Ṛg Veda who begins to see himself as the god Indra (earning the wrath of the thunderer), the fan’s identification of self with the object of veneration can become so great that the boundary between observer and observed dissolves. For the most dedicated, even the mildest critique of the work is perceived as an intensely personal attack on the fan.

Does Wagner’s well-documented anti-Semitism surface in his operas? Do Tolkien’s “quite obviously” Jewish dwarves embody anti-Semitic stereotypes? The true fan will not only deny it but will furiously denounce the person daring to suggest an affirmative answer.

Fundamentalist adherence

The conclusion of Stravinsky’s argument is deeply relevant to our current cultural moment. Written as Nazi Germany was expanding and the Axis powers were ascendant, Stravinsky’s polemic against the sacralization of the artwork ends with a turn to the political developments of his time.

But is it at all surprising that such confusion should arise at a time like the present, when the openly irreligious masses in their degradation of spiritual values and debasement of human thought necessarily lead us to utter brutalization? People are, however, apparently fully aware of the sort of monster to which the world is about to give birth, and perceive with annoyance that man cannot live without some kind of cult. An effort is therefore made to refurbish old cults dragged from some revolutionary arsenal, wherewith to enter into competition with the Church.

We again find ourselves living through a time of cultic thinking and fundamentalist belief creeping into public life.

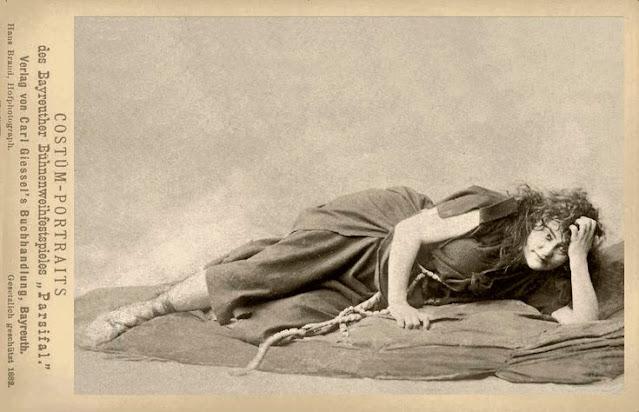

|

| Amalie Materna as Kundry in 1882 Bayreuth production of Wagner’s Parsifal |

Within the online world of Heathenry, differing theological views are denounced as blasphemy (seemingly without any sense of historical irony). Inside the Twitterverse, academics posting about their research are swamped by roving gangs of anonymous mansplainers who pose endless rhetorical questions that no sane answer can satisfy. Across social media, virtual communities of intent form to affirm preconceptions and reinforce prejudices, from Facebook support groups for racist police officers to a Russian social media platform where American neo-Nazis build international contacts.

In all of these examples, critical thinking has given way to the fervor of fundamentalism. Whether the doctrine is religious or political, adherence to its precepts overrides all rational evaluation. Questioning of basic assumptions leads to denunciation by the group and excommunication of the individual, a process that strengthens groupthink as the membership in the group becomes refined down to a harder core.

We now see this process exploding from the virtual world into the regular world.

During the election, Trump’s supporters brushed aside accusations of sexual assault as politically motivated and denounced any who even slightly questioned his proclamations as traitors who wanted the communists to win. During the election, Biden’s supporters brushed aside accusations of sexual assault as politically motivated and denounced any who even slightly questioned his candidacy as traitors who wanted the fascists to win. Grossly anti-Semitic imagery, homophobic declarations, and racist symbols are proudly displayed by furious protestors demanding the end of coronavirus mitigation measures and refusing even the most common-sense safety practices. Scapegoats abound as conspiracy theories and in-group loyalty trump all rational discussion.

Steven Colbert’s truthiness has been succeeded by a belief that reality itself is a matter of opinion, not in a theological sense of maya versus brahman – of illusion versus ultimate reality – but in a very basic and everyday way.

If the president says something is absolutely fake that he said was absolutely real just minutes earlier, and his supporters believe both statements are akin to holy writ, what is real? If #BelieveWomen and #MeToo are inherently powerful and essentially undeniable when the offender is a Republican but abused women are shouted down as gold-digging liars and political tools when the offender is a Democrat, what is real? If the coronavirus is simultaneously a leftist hoax designed to take away your guns and an unstoppable danger that requires trillions of dollars in corporate handouts, what is real?

Doublethink is the order of the day as groups across the political spectrum descend into a madness of fundamentalist adherence to whatever doctrine the day requires.

Modern Pagans declare support for diversity and inclusiveness while embracing sectarian tribalism as a positive way of structuring religious communities. White conservatives in central Michigan fly the Confederate Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia while demanding stoppage of best practices for minimizing the number of coronavirus deaths in their own community. The party that trumpets its belief that “all Americans have an unalienable right to life as stated in The Declaration of Independence” insists that “[t]here are more important things than living” and dead civilians (particularly dead grandparents) are a fair trade for business profits. The “party of inclusion” puts forward the most diverse Democratic primary field in history before choosing the elderly, white, straight, male, Christian multimillionaire.

A doom of our own making

The epitaph of this age of ours is likely to be “my party, right or wrong,” whether the party is political, religious, racial, or what have you.

To point this out is not to indulge in whataboutism, to say that there is no real difference between political ideologies. Quite the opposite. It’s the willingness to wallow in the basest sort of attacks on the other/outsider paired with the resolute refusal to allow any open discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the home team that results in the atrophy of the critical faculty. We tell college students that they must take humanities courses to develop their critical thinking skills, but what living models do they have when so much of public life is built on slandering the other side and dehumanizing the dissenter?

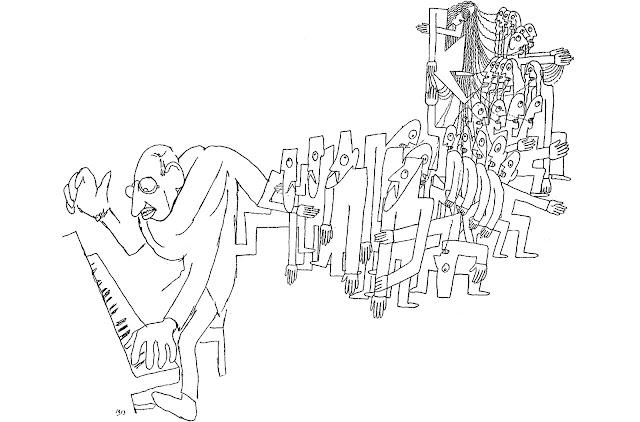

|

| Igor Stravinsky plays Le Sacre du printemps (“The Rite of Spring”) in a 1913 cartoon by Jean Cocteau |

In the current overheated environment, there seems to be a fear that admitting any fault at all is handing ammunition to the enemy. Don’t worry, we’ll fix our own problems later. We just need to win this election, promote this conference, get these membership numbers up, finish whatever project in the now that we’ve set up as the one thing that must be accomplished at all costs. The dream is deferred, the underserved are labeled as special interests, and the status quo rumbles on.

It doesn’t have to be this way. It is possible to be reflective about one’s own group while still standing strongly against real wrong. Somehow, we need to cultivate the inner voice that stops the fingers about to type the bullying, the harassment, and the death threat. We need to build the internalized critical apparatus that asks if the thing we are about to do is truly of worth and worth doing.

We are burning up in a blazing sea of hot takes pouring forth from the endless stream of social media opinions, deceptions, and lies, from the so-called coronavirus briefings that descended into hate rallies, and from our friends and family who insist we must vote for their chosen candidate, or everything terrible to come is our own individual fault. We need a cool breeze to bring us to our senses so that we can climb out of the heat and reflect on what we can all do to move forward out of this mess.

Stravinsky writes of living in a moment when “degradation of spiritual values and debasement of human thought necessarily lead us to utter brutalization.” In our own moment, how can we elevate spiritual values and enhance human thought so that we’re able to move to higher ground? Can we find the answers to today’s problems by turning yet again to ancient texts, or do we need new words to find new solutions? How can we improve our educational systems and social systems so that they develop engaged citizens instead of enraged strangers?

It is difficult to think of engagement in an age of stay-at-home orders and social distancing, at a time when conversations occur on Zoom or through facemasks of dubious efficacy, but the fact that it is now difficult makes it imperative that we do. Will we come through this era-defining trial determined to work together to drive fundamental and consequential change for the better, or will we crawl through with a hardened determination to screw the other guy?

Committing to real change is especially hard for anyone convinced that a holy text is inerrant, that the gods speak truths directly into their ears, or that the leader of their particular group can do no wrong. Stravinsky writes that “one cannot imagine a believer adopting a critical attitude towards a religious service” and warns of the danger of such a species of true and unshakable belief growing in the public realm.

Are we still capable of adopting an attitude that is constructively critical, or are we doomed to slouch towards a Ragnarök of our own making?

An earlier version of this article appeared at The Wild Hunt.