If you’ve been paying attention to our Power Broker series, then you know that bad infrastructure can cause harm. That makes it all the more important to recognize the thought and care that goes into the objects we use and see everyday. Nothing embodies that spirit of recognition more than the history of manhole covers in Japan. Note: this episode is made possible by PNC Bank, who believes—as we do—that the most remarkable designs are often the ones that are most overlooked.

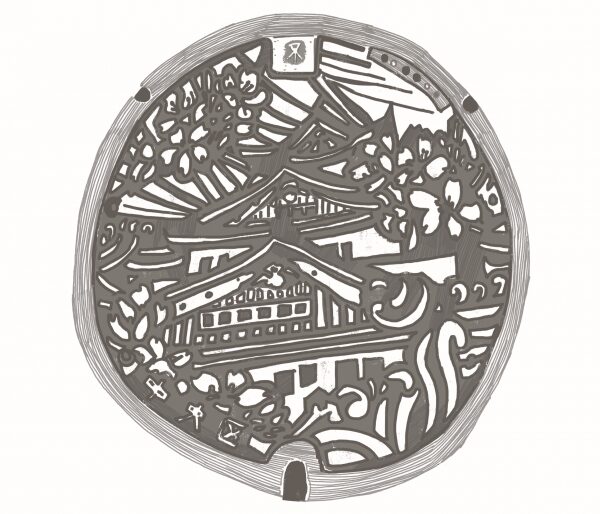

Though Japan is one of the most thoughtfully designed countries in the world, even the people living there need to be reminded of the miracle of reliable infrastructure. In Osaka, Japan lies what may be the loveliest manhole cover ever; it looks like an ornately etched woodblock print. This cover was commissioned in the 1980s to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the modern sewer system. It’s not the only one of its kind–colorful illustrations of various styles adorn stylized manhole covers across Japan.

Yasutake Kameda, a ranking construction ministry bureaucrat, was behind the rise of colorful manhole covers. At the time, just over half of Japanese households were connected to municipal sewer systems. Kameda wanted to raise awareness for the system, in part to get locals onboard for a modern expansion. He encouraged towns and cities to develop location specific motifs for their manhole covers. The tactic worked, and manholer mania was born.

The various designs have some features in common that offer practical safety solutions. For example, a cross-hatching technique offers traction to prevent wheel slippage on wet metal surfaces. Tapered designs rattle less than conventional round covers when they are driven over, reducing noise pollution. For areas that are prone to flooding, special hinge lids were made to be able to flip up while remaining attached to the road so that it can fall back into place when danger passes.

Japan isn’t the only place with distinctive manhole designs. Nashville, Tennessee and New Hampshire both have triangular manhole covers that point in the direction of the subsurface water flows. The covers in Seattle, WA feature embedded city maps, with the raised grid also functioning as an anti-slip element. But even the plain, standard U.S metal manhole cover has a beauty to it. It’s worth getting excited about underground water and sewage infrastructure, even if the covers near you aren’t painted, like in Osaka.

Alvord Lake Bridge

There’s something about rebar that is fascinating, perhaps because it invokes the rare fear of being skewered. Metal reinforcement bars dovetail with a unique structure in San Francisco — a tiny bridge on the eastern edge of Golden Gate Park called the Alvord Lake Bridge.

Ernest Ransome, the father of modern rebar, constructed the bridge in 1889. Today, it is a dumpy, cracked, and neglected structure. The inside is a surreal tunnel of phony stalactites.

But the Alvord Lake Bridge is, quite literally, the bridge to the modern world. It is one of the oldest reinforced concrete structures still standing. The twisted iron bars embedded in the bridge served as the model for all the rebar containing structures that followed. It is the ancestor to an endless number of reinforced concrete buildings, bridges, tunnels, viaducts, and foundations. Ransome’s major innovation in rebar was to twist the square bar so that it bonded to the concrete better.

Concrete has incredible compression strength, but it does not have much tensile strength. So if you want concrete to span any significant distance, you need to embed metal reinforcement.

There are plenty of candidates for the most overlooked, most invisible part of the built world, but reinforced concrete has a good claim to being the most invisible of all. Because if it’s made right, you never see the steel skeleton underneath all the concrete structures that you work in, drive over, and walk under.

The problem with steel reinforcement is that it rusts. When the steel begins to rust, the bond with the surrounding concrete is broken. The rusted metal also swells and breaks the concrete apart. Because of this, most of the reinforced concrete structures that are constantly exposed to the elements (like our highway system) were only designed to last 50 years. More advanced concrete mixtures and epoxy coated rebar increase the longevity, but without regular maintenance, entropy eventually wins out.

Ernest Ransome left San Francisco soon after he completed the Alvord Lake Bridge. In his book “Reinforced Concrete Buildings” published in 1912, you can detect a tinge of bitterness in Ransome’s text as he describes how his twisted rebar was “laughed down” by the Technical Society in California. He left for the east thinking that his revolution of reinforced concrete would have a better chance out there. He left thinking that no one here would fully appreciate his Alvord Lake Bridge, his bridge to the modern world. And looking at it today, I’m sad to say, he was right.