I’ve known about Darkseid at least since he appeared on the cover of the first issue of DC Comics’ Super Powers in 1985. Since then, I’ve read dozens of comic books featuring the dark master of Apokolips and all the associated New Gods created by Jack Kirby.

When yet another reboot of Superman comics introduced Lex Luthor’s Apokoliptian armor and use of a Mother Box, I realized that I’ve never really had a particularly clear grasp of Kirby’s whole DC mythology. I know who the characters are, I know about the strange melding of mysticism and technology, but I’ve never really felt like I fully understood what all the fuss and bother with these strange figures was all about.

I decided to pick up a used copy of the first volume of Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus to start at the beginning and see if I could get a better understanding of the weirdness.

|

| Mythological works of Jack Kirby (photo by Karl E. H. Seigfried) |

From the first 1970 issue of Kirby’s run on Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen – the bizarre choice for Kirby to launch his new mythology after arriving at DC – it was clear that breaking free of the leash that Marvel editor Stan Lee held on his creativity led to some fundamentally strange storytelling.

As writer, artist, and editor of his own work, Kirby brought back the Newsboy Legion – a corny gang of kids he had co-created for DC way back in 1942 – even as he began introducing freakish concepts of hidden conspiracies that would quickly blossom into the complicated plot of what DC called (without explanation) the “Fourth World” storyline, which wound through the Olsen series plus the Kirby-created titles The Forever People, The New Gods, and Mister Miracle.

By the time the first issue of The New Gods arrived in 1971, Kirby had already introduced Darkseid and several of his accomplices, a secret federal genetic lab known as the DNA Project (morphed into Project Cadmus by DC after the 1985 Crisis on Infinite Earths series), a big green Jimmy Olsen that veered awfully close to copyright infringement on the Hulk (co-created by Kirby for Marvel), a new version of the Guardian (another 1942 DC co-creation of Kirby), a group of New Age hippie teenager gods from space in the form of the Forever People of New Genesis, and the mystical female sentient computers known as Mother Boxes.

It was clear that DC was giving Kirby free rein to spin out his strange visions of society, science, space, and spirituality, but things took a surprising (to me, at least) turn in that first issue of The New Gods.

| The fall of the old gods, from the first issue of The New Gods by Jack Kirby |

In a two page prologue titled “Epilogue,” Kirby writes,

There came a time when the old gods died! The brave died with cunning! The noble perished, locked in battle with unleashed evil! It was the last day for them! An ancient era was passing in fiery holocaust!

The full-page illustration shows figures who look an awful lot like the Asgardian gods Kirby had drawn for Marvel from 1962 until 1970. There’s even a shadowy portrayal of a powerful figure in a winged helmet wielding a short-handled hammer.

Kirby continues with a description of “the home of the old gods” being torn asunder into two halves and accompanies it with a drawing of an island in outer space with an outline that looks suspiciously like that of the version of Asgard he had long illustrated over at Marvel. The two halves of the old gods’ dwelling become the paired planets of New Genesis and Apokolips, the domains of Highfather and Darkseid, and new deities that arise to take the place of the old.

From Asgard to Apokolips

This was the point at which I realized Kirby was giving DC a direct sequel to the sagas of the Norse gods he had produced for Marvel. Indeed, he had already been working on the concept while still employed at Stan Lee’s company, planning out a Ragnarök that would kill off the Asgardians and give rise to new gods of a new mythology. Due to his ongoing and now well-known shafting by Marvel over creator rights and compensation, he refrained from sharing his plans until he had moved over to the Distinguished Competition.

The Fourth World mythos is a direct continuation of Kirby’s long project of bringing the gods of Norse mythology into modern settings – a project dating back to at least 1941, when Kirby created a version of the Roman god Mercury for Timely Comics who was soon renamed Hurricane and declared to be “son of Thor, god of Thunder.” In 1942, Kirby drew an incarnation of Thor with red beard and horned helmet for DC’s Adventure Comics, then created another bearded Thor in 1957 for DC’s Tales of the Unexpected. His deepest dive into the mythology of the Eddas was, of course, his long run on Marvel’s The Mighty Thor and its backup feature Tales of Asgard.

After seeing the Norse connections of Kirby’s 1970s material for DC, I picked up the insanely huge complete compendium called The Fourth World Omnibus. Containing all of Kirby’s New Gods tales from 1970 through 1985, the weight of the 1,481-page monstrosity felt like it was bruising my rib cage when I laid down on the couch to read it. It didn’t disappoint in the deity department.

| Relaxing after Ragnarök, from the seventh issue of The New Gods by Jack Kirby |

The seventh issue of The New Gods, published in 1972, tied Kirby’s new mythology even more deeply to the Norse myths. “In the beginning,” the narration begins biblically,

The New Gods were formless in image and aimless in deed!!! On each of their two new worlds, their races had sprung from a survivor of the old!! The living atoms of Balduur gave nobility and strength to one!! – And the shadow planet was saturated with the cunning and evil which was once a sorceress!!

I’ve written before about the fact that Kirby and Lee sometimes seem to know more about the sources of Norse mythology than prominent academics. I’ve also written about the blend of Judeo-Christian and Norse mythologies the two of them created. Both Stan Lee (Stanley Lieber) and Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg) were born in New York City to Jewish immigrants from Europe, and they both repeatedly mix elements from Abrahamic and Indo-European myths.

Here, Kirby moves easily from the opening words of the Book of Genesis to the final verses of the Old Norse poem Völuspá (“Prophecy of the Seeress”) and their revelation that the god Baldr will rule over a new world of peace after the devastation of Ragnarök. Kirby’s line about the aimlessness of the New Gods in their early days seems to echo the lines in Völuspá about the first age of the Norse gods, when sun, moon, and stars wandered about without knowing their own paths.

If the spirit of the bright god Baldr suffuses the beautiful world of the New Gods, who is the evil sorceress who gives her character to Darkseid and the dark gods of Apokolips? The obvious choice is Kirby’s own Enchantress, an enemy of Thor and sometime ally of Loki in Marvel’s version of Norse mythology. In his Thor comics published late in the first decade of this century, writer Matt Fraction explicitly equated the Enchantress with the Norse goddess Freyja. Did Kirby also make this connection?

In Völuspá, the prophetess speaks of a female figure named Heiðr (“bright”) who makes prophecies, practices sorcery, performs enchantments, and “was always the joy of an evil woman.” She’s usually interpreted to be Freyja, the Vanir goddess who teaches magical practices to the Æsir. Maybe this suggestion of a connection between Freyja, sorcery, and wicked women suggested the idea of the Enchantress to Kirby.

Kirby associates the sorceress progenitor of the Apokolips gods with “cunning and evil,” the core traits of his own Marvel version of Loki. The Old Norse Hyndluljóð (“Song of Hyndla”) has a striking description of Loki being impregnated by an evil woman and becoming the ancestor of every ogress that came after. Perhaps this connection between Loki and ill-working women was also in Kirby’s mind when he conceived the origins of Apokolips.

Loki looms larger in the character of Metron, especially as portrayed in this particular issue. Although one of the New Gods of New Genesis, he strikes a pact with Darkseid and is willing to provide services that harm his original tribe in order to further his own personal ends even as he brushes aside the fact that his double-dealing will “create the means for mass slaughter.”

In the Eddas, Loki is likewise a figure who plays both sides as he moves between the giants of his original tribe and the gods with whom he lives in the mythic present. Like Metron, he shows little loyalty to either side in the cosmic conflict, is motivated by his own needs, and moves everyone down the line to the bloody climax of Ragnarök.

The issue ends with Highfather and Darkseid exchanging hostages to – for a time – end the conflict between their two tribes of warring gods. Snorri Sturluson’s Ynglinga saga (“Saga of the Ynglings”) tells of the similar exchange of hostages that ends the first great mythological war between the god-tribes of the Æsir and Vanir. Given the obvious similarity between the names Highfather and Allfather (an English translation of the Old Norse Alföðr, a byname of Odin) it would seem that the patriarch of the New Gods is a parallel of the patriarch of the Norse gods as portrayed in the Icelandic sources.

|

| Highfather rejects his war-staff and renounces war, from issue 7 of The New Gods by Jack Kirby |

But Kirby’s Highfather is more closely connected to the Old Testament than he is to Old Norse. He bears a staff in the shape of a Mosaic shepherd’s crook, not an Odinnic spear. Indeed, the seventh issue of The New Gods shows him rejecting his “war-staff” as a weapon as he renounces war itself. After he does so, a wall appears in a desert waste and “a hand of flame” writes a message on it, stating that the inheritance of the man who becomes the Highfather is the Source, Kirby’s pre-Star Wars concept of a universal force that courses through the universe.

This fairly obviously refers to the mystic hand that writes on the wall of Belshazzar in the Book of Daniel, delivering God’s message that the Babylonian ruler’s kingdom will be divided. Division also relates to Kirby’s tale, as the exchange of hostages immediately follows and the two tribes of gods agree to stay apart on their own respective planets.

Highfather discards his staff of war and carries a staff of peace, eventually – at the conclusion of The Hunger Dogs, the 1985 graphic novel at the end of the Omnibus – raising his staff meaningfully as he leads the New Gods in search of a new home for his tribe in a not altogether subtle reflection of Moses as a shepherd leading the Israelites away from oppression and towards their eventual home.

So if Highfather is Kirby’s new Moses, where is his Odin?

Odinnic fury and a Broadway star

The same issue shows that Darkseid’s young son Orion has been given to Highfather as part of the hostage exchange. He grows up to be the great warrior prophesied to bring down Darkseid himself. Throughout his Fourth World mythos, Kirby portrays Orion as a figure whose rage continually threatens to overwhelm him. He pushes his allies aside in his furious determination to gather information that will enable him to win victory over his enemies and wreak bloody havoc as he obsesses over the prophecy of the final battle and his own ultimate fate.

Odin’s very name has etymological roots in terms for fury and madness, and his berserker devotees are defined by their overwhelming rage. I’m one of many people who give precedence to the Icelandic images of Odin as a wandering sharer of wisdom and inspirer of creativity, but he is also the bloodthirsty god of war who seeks information about the final battle to come, stirs up violent strife among men, and is identified by the medieval German chronicler Adam of Bremen as “Wodan, id est furor” (“Wodan, that is fury”).

It is this darker aspect of the god – himself the son of a giantess and the grandson of a giant named Bölþorn (“evil thorn”) – that Kirby transmutes into Darkseid’s universe-traveling son Orion, willfully mashing up Greek and Norse mythology as he names his Odinnic character for the Greek hunter.

Kirby may have chosen this particular mythic name to connect his character with Odin as the leader of a form of the Wild Hunt, but a penchant for Greek-Norse hybridization is already evident in his 1941 tales of Mercury, son of Thor. Even in this, he echoes Snorri’s Edda, with its insistence that the Norse gods can be traced back to the legendary heroes of the Trojan War.

Kirby also seems to be following Snorri in his portrayal of Lightray, the bright and shining god of New Genesis who dresses all in white and refuses to engage with the dark fury of Orion’s single-mindedness and bloody-mindedness. Much of Kirby’s characterization of Lightray parallels Snorri’s introduction of Baldr in the Edda:

He is so fair in appearance and so bright that light shines from him, and there is a plant so white that it is called after Baldr’s eyelash… He is the wisest of the Æsir and most beautifully spoken and most merciful, but it is one of his characteristics that none of his decisions can be fulfilled.

With only the smallest of changes, this could be modified to describe Lightray, the bright one whose words of peace are furiously brushed aside by the raging Orion.

And what of Thor?

At the end of the 1960s, shortly before he left Marvel, Kirby made a series of presentation drawings showing radical reworkings of the cast of The Mighty Thor. The character and costume designs show a conceptual midpoint between his 1960s Marvel gods and his 1970s DC deities. He was clearly thinking of new directions for the thunderer, and two very Thor-ish, but very different, figures appear in his Fourth World epic – one male and one female.

In a backup feature paralleling his old Tales of Asgard series for Marvel, the 1971 fifth issue of The Forever People features Kirby’s introduction of a New God named Lonar who wanders alone (hence his rather transparent name) through the ruins of Asgard on New Genesis in search of remnants of “the elder gods.” He finds a “battle horse” of the past era who is given the name Thunderer in Lonar’s next backup feature, two issues later.

Perhaps echoing the hostility between Thor and Odin in the Old Norse Hárbarðsljóð (“Song of Graybeard”), the horse rears up and bolts when touched by Orion. Or maybe the horse, a survivor of one Ragnarök, recognizes that Orion is destined to bring about another.

|

| Lonar wears “the trappings of the elder gods” in Hunger Dogs by Jack Kirby |

When Lonar reappears thirteen years later in the graphic novel that brings a form of closure to Kirby’s mythology, he is drawn like a slightly redesigned version of Kirby’s Marvel Thor – a design much closer to the 1960s character than to the proposed updates Kirby created before leaving for DC. Lonar’s long hair flows from beneath a winged helmet as he returns to the city of the New Gods and Highfather remarks, “Don’t you look splendid in the trappings of the elder gods!” and tells him that he’s “not the first to be intrigued by the ancient past.”

As with several of Kirby’s characters – he openly said Ben Grimm of the Fantastic Four was a self-portrait – Lonar seems to be a reflection of an aspect of the artist’s self. In this case, he is an acknowledgement of Kirby’s lifelong love of ancient mythology and its tales of gods and heroes.

That said, the character who seems the most direct descendant of Marvel’s Thor in DC’s New Gods is Big Barda. She appears in all her glory on the first page of the 1971 fourth issue of Mister Miracle, wearing armor and helmet heavily stylized in the Kirby manner. Like Kirby’s Thor, Barda is the tank of the party, always ready to rush in and start smashing enemies with her “mega-rod,” an hand-held weapon that – like Marvel’s Mjölnir – isn’t only a blunt instrument, but manifests whatever amazing powers Kirby needs it to have at a given point in the storyline.

She’s arguably the most macho figure of the Fourth World, bringing a direct Thor-like energy to what sometimes devolves into posturing Wagnerian space opera. Big Barda is also the leader of the Female Furies, the bizarre Valkyrie-like force that follows her lead from Apokolips to her adventures on Earth and elsewhere. In 1987, artist, writer, and Kirby devotee Walter Simonson strengthened the Thor-Barda connection when he introduced the new-look Marvel Thor wearing armor that was awfully close in color scheme, concept, and design to that worn by Big Barda.

Given his mixing of mythologies, it’s interesting that Kirby’s direct inspiration for Big Barda was the Jewish Broadway singer Lainie Kazan, then a rising star after stepping in for Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl and being featured in an issue of Playboy. Multiculturalism is a feature of the Fourth World, with three of the series having black characters in the core cast and the other having a prominent recurring African-American character.

“Mugged by the Word of God”

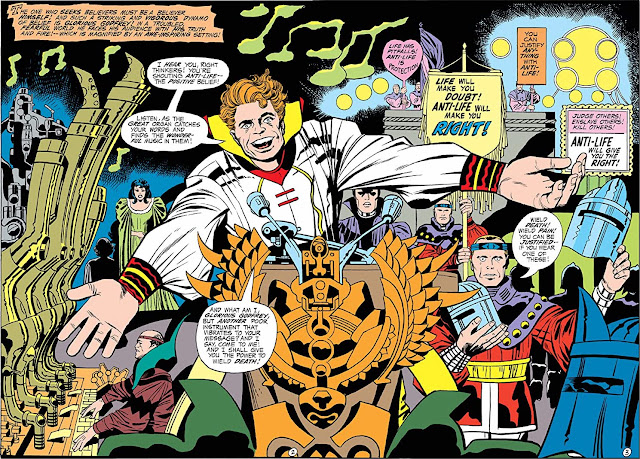

Kirby’s social and political concerns come through in other ways, such as in the depiction of Glorious Godfrey in the 1971 third issue of The Forever People. Based on the anti-Semitic and homophobic evangelical Christian minister Billy Graham, Godfrey smilingly encourages his followers to embrace “anti-life” as he issues helmets that enable them to hide their identities and – with the freedom from morality granted by anonymity – wield brutal violence against those they wish to eliminate.

|

| Glorious Godfrey evangelizes for Darkseid, from the third issue of The Forever People by Jack Kirby |

Kirby introduces Godfrey by showing him standing on a giant stage and preaching of a coming holocaust before smilingly telling his followers that they are superior to those to whom they will bring “Darkseid’s gift of anti-life.” Always ratcheting up his influences to symbolic levels, Kirby portrays Billy Graham’s manipulation of his enormous audiences in cosmic terms.

Sometimes the mythological and sociological influences coincide, as in Kirby’s portrayal of the “bugs,” humanoids who evolve in underground colonies from poisonous “micro-life” sent against New Genesis by Darkseid as the dwarfs of Norse mythology evolve “by decision of the gods” from where they squirm in the flesh of the dead giant Ymir “like maggots in flesh.”

In the 1972 tenth issue of The New Gods, Kirby shows the rulers of New Genesis – as imperfect as the gods of the various Indo-European mythologies – working to eradicate what they see as a lesser race by denouncing them as pests who seek to rise above their station. In case you miss the parallel with the Nazis gassing their Jewish prisoners in extermination camps, Kirby provides disturbing imagery of a field covered with dead and dying as the lone standing figure chokes to death and yellow clouds of gas drift over the scene.

Kirby’s idiosyncratic admixture of the mythological, sociological, and technological sometimes gives the work a prescient quality. At the beginning of his Fourth World saga, Kirby’s portrayal of the Mother Box as a small computer obsessively loved by its owner, always kept close to the body, and turned to for information and help in all circumstances predicts the ubiquity of and intense love for smartphones nearly forty years before the appearance of the first iPhone.

At the end of his epic, Darkseid becomes almost pathetic as he laments the rise of Micro-Mark, the new technology developed for him by the deviant New Genesis god named Esak that seems to portray digital technology and/or nuclear weapons. In 1985, the year the Hunger Dogs graphic novel appeared, Microsoft released its first iteration of Windows and began the digital transformation of postmodern life even as the Air Force began testing its Mid-Infrared Advanced Chemical Laser as a possible defense against incoming nuclear missiles. As always, Kirby reworked his concerns about real-world developments into symbolic form.

In his introduction to the first book of the multi-volume collection of the Fourth World comics, Scottish writer Grant Morrison discusses the effect of first attempting to read this material at age eleven. Kirby’s tales, he writes,

operated at a higher frequency than my pre-adolescent brain was wired up to match; his operatic visions of burning planets and snarling sci-fi deities left me with an inner shudder of the numinous and uncanny. Kirby’s dramas were staged across Jungian vistas of raw symbol and storm…. Kirby was too wild, too creepy, too raw.

He describes “experiencing a near-religious sense of awe and terror” and feeling like he’d “been mugged by the Word of God and somehow walked away.”

Despite being thirty-five years older when I first read this material, I had a similar experience. At every step, I felt like Kirby’s tales manifested at the level of mythology, of myth as described by the French philosopher and theologian Paul Ricœur as “symbols developed in the form of narrations.”

In Kirby’s sprawling epic – improvised and willed into material form as he furiously created page after page and issue after issue for year after year – the narrative is often difficult to follow, the dialogue is many times obscure, the motivations of the characters are regularly unclear, good and evil are sometimes not so clearly delineated, death is always a threatening presence, and there constantly seems to be some deeper symbolic meaning that is just out of reach behind the surface action.

Kirby really was transcending the medium in which he worked and creating a new mythology that followed and built upon the ancient Norse mythology that he so long and so deeply loved. Like the myths of ancient times, Kirby provided no key to decode his symbols – even though DC later attempted, in Snorrian fashion, to explain away all the inherent uncanniness of his vision as they sanded away the rough edges to fit Kirby’s characters into the mainstream of their own corporate mythos. Also like the old myths, Kirby’s work both expresses the deepest concerns of his time and speaks to the worrying aspects of our own age.

|

| 1944 self-portrait by Jack Kirby, colored by Rob Steibel |

Last year, I wrote about baseball player, author, and activist Jim Bouton as one of my personal saints. The other very human individuals I consider in that category are John Coltrane, Jack Kerouac, and Malcolm X – all of whom challenged themselves to be greater while publicly speaking out against the failings of their own society. After reading the Fourth World saga and Mark Evanier’s excellent illustrated biography Kirby: King of Comics, I’ve now added Jack Kirby to that short list. Like the others, he is a prophet – not only in the sense of speaking of things yet to come, but with the meaning of being inspired with deep spiritual insight.

There’s much more to be said about Jack Kirby. As lengthy as this article turned out to be, it barely scratches the surface. Hail to the king of comics!

An earlier version of this article appeared at The Wild Hunt.