Every so often, one of the college students in my Norse mythology classes raises a hand and asks, “Which eye did Odin give up to drink from Mimir’s well?”

Related questions include which side of Hel’s face is the corpse side, what the size measurements of Freyja’s cats are, and what the design specifications of Loki’s mistletoe missile are.

|

| Odin, Sleipnir, Huginn, and Muninn by Gerhard Munthe (1849-1929) |

My first, gut reaction to this type of question was to reply that mythology functions differently from fantasy.

Myth is vague where modern fantasy novels give page after page of specific details. Myth is elusive and allusive where tabletop role-playing games qualify and quantify every characteristic feature in overwhelming detail. Myth compresses action into stark imagery where video games expand conflict into endless hyperreal performances.

Students raised on Harry Potter, Dungeons & Dragons, and World of Warcraft may find mythology disappointingly diffuse. So many myths lack direct speech or dialogue in the modern sense. There is often no sense of the characters having inner lives, and motivations can range from totally banal to utterly incomprehensible.

In Norse mythology, physical descriptions of mythological figures are few. Some of the details we are sure we have read are actually akin to mass hallucinations, as in the widespread idea that Thor has a red beard in the Eddas. He does not.

The image of the red-bearded Viking Thor comes from the Icelandic sagas, historical and fantastic prose fiction composed two centuries and more after the nation’s public conversion to Christianity and written in imitation of new forms of literature filtering up from the Christian continent.

Red Thor appears in strikingly Christian contexts, as a threatening figure of the pagan past who seeks to flip new converts back to the Old Way. Any similarities to the red devil are purely non-coincidental.

Yet the meme of the red-bearded Eddic Thor has long been embedded into the writing of even the scholarly giants of Scandinavian studies, in their standard dictionaries and public publications.

Christian accretions and pagan cores

There seems to be something in the modern mind that craves specificity, that imposes concrete imagery onto textual traditions where that type of descriptive writing does not exist.

Or perhaps it’s not so much an issue of the modern mind but of the post-pagan, post-polytheistic perspective. Snorri Sturluson, thirteenth-century author or compiler of what we now call the Prose Edda, determinedly included or invented small descriptive details that are not present in the poetic sources he prosified.

The closer we get to the present, the more people seem to crave these sorts of details. From the retellings by William Morris in the nineteenth century to the transformations by J.R.R. Tolkien in the twentieth to the repackagings by Neil Gaiman in the twenty-first, the Snorrian impulse to muddle about with the texts and fill in the gaps seems irresistible.

So much of modern reading of ancient myth views it as literature, as something that sits on the same shelf as the fairy tale and the fantasy novel. There is indeed a hostility in some parts of academia and some branches of postmodern Ásatrú and Heathenry to viewing the surviving Norse myths as at all religious, condemning them instead as products of medieval Christian authors that present hopelessly muddled and willfully distorted versions of what may never have been pagan tales in the first place.

In a nutshell, the counterargument (of which I am a determined proponent) acknowledges the general scope of this criticism but counteroffers the mountain range of corroborating evidence and explicative theory from archaeology, linguistics, history of religions, and neighboring fields to argue that what Christian accretions have been sprinkled over the myths do not nullify the pagan mythological core at the heart of the surviving texts.

It is the very turning away from reading the myths as literature to reading them in the wider context of specifically religious texts of related world religions that leads to a better answer for those students asking about eyes and faces, cats and mistletoe.

India and Iceland

“Wodan,” wrote Adam of Bremen in the eleventh century, “id est furor.” Wodan is fury, as his Icelandic counterpart Odin is furious (etymologically speaking). There are many historical accounts and semi-historical saga descriptions of bloody sacrifices to the bloodthirsty god who is often connected to the causes, manifestations, and consequences of killing and war.

Yet the image of Odin as the wandering wizard endures, shaped into the Wanderer by Richard Wagner and morphed into Gandalf by J.R.R. Tolkien. How do we reconcile the furious figure who hovers over the battlefield with the wise walker along ancient paths?

Thousands of miles span the distance from India to Iceland, and thousands of years passed between the composition of the Mahābhārata and the transcription of the Norse myths, yet the parallels between the Vedic and Eddic mythologies have been known, studied, and disputed since Sir William Jones laid out the connections between Germanic, Indic, and other surprisingly related language groups in 1787 as the Indo-European theory was first formulated.

Jones was part of the British colonial administration in India, and his theories were filtered through the Romantic nationalism of the nineteenth century to provide theoretical, rhetorical, and propagandistic fodder for the Nazi horrors of the twentieth.

The old ideas of blond Aryan hordes riding out of the Caucasus to conquer the world have rightfully and righteously been dragged into the trash icon of academia’s shared desktop, but the fact of linguistic, cultural, ethical, mythical, and religious connections between members of the wider Indo-European family remain.

My copies of the ancient Sanskrit texts from India are covered by smudgy spiderwebs of my penciled notes, such as “cf. Hávamál,” “cf. Völuspá,” “blót,” and “reciprocal gifting.” On nearly every page of every text I’ve studied, there are amazing parallels to the Norse material, from outlines of myths shared by Indra and Thor to very specific healing spells that appear in ancient India as they do in medieval Germany.

These finds can be so exciting to someone as excitable as me on these subjects that, at one point while I was in divinity school, Prof. Wendy Doniger had to limit me to a set number of “ooh, this is just like that bit in Norse myth” exclamations in each class session.

It was one of these moments in class that enabled me to provide my own students with a deeper answer to their questions about Odin’s eyes and to find for myself a more meaningful understanding of the wide disparity between the war-inciter and the wanderer.

Cold feet

By the sixth book of the Sanskrit Mahābhārata, the warring parties whose rivalry has consumed the preceding five books are finally ready to face off in their ultimate battle. In the last moments before the combat begins, the great and supremely macho hero Arjuna gets cold feet.

Looking across the battlefield, he sees that both armies are composed of his own “fathers, grandfathers, teachers, uncles, brothers, sons, grandsons, companions, fathers-in-law, and friends.” Consumed with compassion and despair, he tells his chariot driver that he will not fight against his own family members, and he throws down his bow and arrows.

His chariot driver tells him that he is behaving in an unworthy manner and warns him against becoming klība, a Sanskrit term with a range of meanings focused on “unmanliness” that is similar to the Old Norse ergi. “Shake off this miserable weakness of heart and get up,” the driver admonishes the languishing hero.

When Arjuna continues to complain of his concerns, his chariot driver begins an enormously lengthy lecture not only on the responsibilities of the warrior, but on a host of increasingly esoteric religious teachings.

In fact, the chariot driver is the god Krishna, and the teachings he recites to Arjuna are the sacred text known as the Bhagavad Gītā (“Song of the Lord”).

After Krishna finishes one section of his lessons for Arjuna by declaring that there is “no end to [his] divine manifestations,” the hero responds:

You are just as you have described yourself, great lord; but I wish to see your majestic form, supreme person. Master, if you think I will be able to see it, then show me your imperishable self, lord of yoga.

Krishna agrees to reveal his forms to Arjuna “in their hundreds and thousands: diverse, divine, and of many colors and shapes.” He tells the reluctant warrior to observe “the whole universe with its mobile and immobile aspects concentrated within [his] body.”

Because this vision is too great for human eyes, he grants divine sight to Arjuna.

It’s all too much

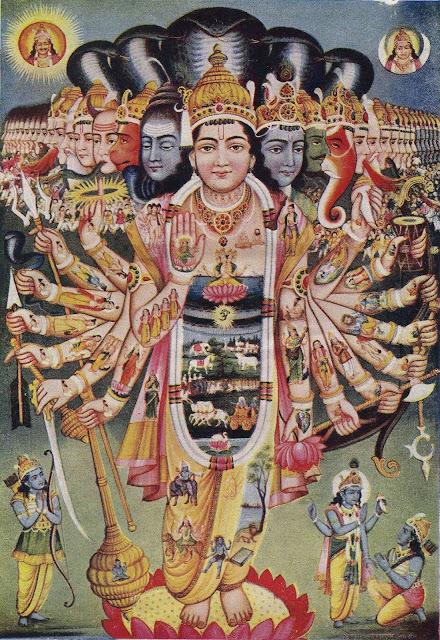

The narrator describes Krishna’s “supreme, majestic form” as revealed at that moment.

With many mouths and eyes and numerous wonderful aspects, with multiple divine ornaments and raised divine weapons, it bore celestial garlands and robes and was anointed with divine perfumes, composed of all marvels, godly, infinite, and facing all directions. If the light of a thousand suns rising at once were to appear in the sky, it might resemble the splendor of that great soul. [Arjuna] saw the entire universe with its various divisions concentrated there in the body of the god of gods.

Arjuna bows his head and speaks mighty words in praise of Krishna’s great cosmic beauty, but he soon begins to testify to the great panic and enormous fear he feels when he sees Krishna’s “mouths like the fire of time” into which all the “heroes of the world of men” rush into “like the many rivers running into the sea,” to be crushed and devoured. As revealed to Arjuna, the “blazing mouths” of Krishna devour “all peoples, all worlds.”

|

| Krishna reveals his cosmic form to Arjuna in an Indian illustration from the early 1900s |

Krishna responds to Arjuna’s fear by declaring, “I am Time, the world destroyer, ripened, and here I am busy crushing the worlds.”

The hero again bows, praises Krishna, finally realizing that the chariot driver he has palled around with is actually the mightiest of all deities.

Arjuna apologizes for past familiarities and begs for an end to the overwhelming cosmic vision, asking Krishna to revert to a limited form that can be comprehended with normal human senses – to conform to the common image of the god as a young man with diadem, mace, and discus. “Change into your four-armed form, thousand-armed god of universal form!”

Krishna obliges, and the lesson continues.

Fury itself

I’m not saying that Krishna is a parallel of Odin, and I’m not placing an equal sign between the Krishnavite “Song of the Lord” and the Odinic “Sayings of the High One.”

At least as regards the larger question at hand in this particular article, I’m not as interested in the specificities of the god or the teachings being promulgated as I am in this notion of a cosmic divinity too immense to be comprehended – a “god of universal form” that must shrink down into a conventional form so that we humans of merely mortal perspicacity can conceive of it without our brains melting.

When Krishna takes his guise of a human charioteer, he is a comforting figure who guides and helps. When he is in his regular religious depiction as a four-armed anthropomorphic deity with traditional weapons, he remains comprehensible. It is only when he reveals his ultimate universal form that he becomes overwhelming and terrifying.

In this light, there is an insight into the figure of Odin and the contradictions of his portrayals. It’s quite easy to follow the shape of the above paragraph and apply it to the Norse god.

When Odin takes his guise of a human wanderer, he offers advice and shares wisdom. When he is in his regular religious depiction as the far-seeing anthropomorphic deity on the high seat above, he remains comprehensible.

The final step, however, is often missing. It is only when he reveals his ultimate abstract form as fury itself that Odin becomes overwhelming and terrifying.

The surviving Old Norse texts do not contain the detailed theological discussion that is so deeply woven through the Sanskrit sources, so we are left to formulate this form for ourselves. Since it’s not clearly portrayed in the texts we have, where do we find the greater, non-anthropomorphic form of Odin?

Odin is there

Again, the “Song of the Lord” gives a hint. Krishna makes clear to Arjuna that he is in all the world and that he abides in all beings. I believe that we can find Odin within ourselves, for better or worse.

He is the fury that stirs poet, artist, dancer, and musician as they enter into a deeply creative state in which they lose track of time and mundane situation. When the guitarist is so concentrated on improvising in the moment that she doesn’t afterward remember making any conscious musical decisions, Odin is there. When the painter is so immersed in the work that she doesn’t notice the night’s passing until the beeping of her morning alarm finds her still brushing away, Odin is there.

He is also the fury that stirs runner, boxer, gymnast, and baseball player as they find the zone where conscious thought gives way to inspired action. When the boxer senses that the moment has come and explodes into a flurry of blows from all angles that brings the knockout, yet doesn’t feel or realize that his own nose is already broken, Odin is there. When the baseball player perceives the ball as floating gently over the plate in slow motion and hears no sound within an internal quietude as he slams the ball out of the park, Odin is there.

The overtaking of the conscious mind is not always so beautiful. Odin is also there when the abuser sees red and hurts without control. He is there when the police officer succumbs to fear and hate and empties his weapon into the back of a child. He is there when the soldier sees a friend fall and his mind snaps free of anything that would restrain his indiscriminate revenge. This is the truly overwhelming and terrifying Odin.

What all of these experiences have in common is the feeling that something has entered the mind and overwhelmed everyday thought. Seeing red, entering the zone, getting lost in the creative moment – all have a sense of drunkenness about them, of intoxication.

The Norse myths capture this feeling by telling us that Odin lives on wine alone and shares out the mead of poetry that inspires the mind of the one who drinks it. The tenth-century Icelander Egill Skallagrímsson famously rails against the bloodthirsty Odin for taking the lives of his sons but thanks him for the gift of poetic skill that allows him to express his grief.

Gather around the table

But this is all too abstract and has too many different individual manifestations, from the passion of the painter to the rage of the killer. It is also far too terrifying. Who among us would be able to gaze into the eyes (or even one lone eye) of the power of unrestrained fury itself?

So we shrink Odin down into a form in which he is more comprehensible, more understandable, and more relatable.

Although his eye may flash with fury from time to time, the wanderer with his beard, hat, cloak, and walking stick is someone we can look forward to meeting. How wonderful would it be to sit by a forest brook and listen to the wise wizard share his wisdom?

Finally, there is a better answer I can give to my students when they ask about Odin’s eye.

The specifics are up to the storyteller and to the one who hears the story. Imagine the gods as the tales inspire you, but always remember that Odin is not the wanderer. He is not the regal figure on his high seat. These are forms that he takes so we can comprehend him or forms in which we conceive divine powers so we can engage with them.

Enjoy the myths, but remember that – as the philosopher Paul Ricœur wrote long ago – myths are made of symbols interacting in narrative form.

Both historically and in today’s world, reading myths literally leads to a fundamentalist mindset with all of its awful outcomes. If we instead agree to gather around the table and discuss what meanings may lie behind the myths, maybe we can have a conversation about leading better lives together.

Quotations from the Bhagavad Gītā are from Mahābhārata, Book Six: Bhīṣma, Volume One, translated by Alex Cherniak (New York University Press, 2008). An earlier version of this article appeared at The Wild Hunt.

![The Post Malone Experience (FBF) [VIDEO]](https://xxpodcastxx.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/4b6820cb8abcd9a6b8ef7a929b26d812-360x360.jpg)