Today, we have three stories about designs meant to fool you. Camouflage meant to fool U-boats. Highways designed to fool your brain into going way faster than it should want to. And impeccably made fake signs meant to guide you to the right freeway. Three classic, favorite 99PI’s completely updated, remixed, and rescored.

Razzle Dazzle

Listener Dylan Frey created a zine version of this episode. See it here: Razzle Dazzle Zine

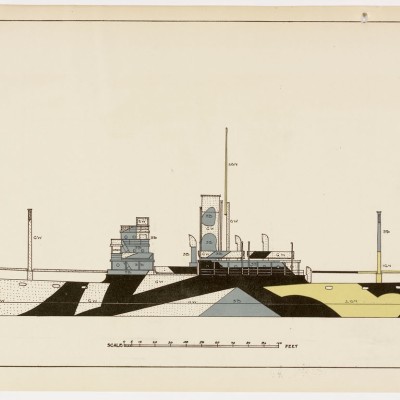

This is probably not what you think of when you think of camouflage.

Becoming invisible with your surroundings is only one type of camouflage. Camofleurs call this “high similarity” or “blending” camouflage. But camouflage can also take the opposite approach.

Think about zebras. It’s hypothesized that their stripes make it difficult for a predator to distinguish one from another when the zebras are in a large herd. The stripes also might make zebras less attractive to blood-sucking horseflies. This is called disruptive camouflage.

When it comes to humans, the greatest, most jaw-droppingly spectacular application of disruptive camouflage was called Dazzle.

Dazzle painting emerged in the 1910s as a design solution to a very dire problem — American and British ships were being sunk left and right by German U-boats. England needed to import supplies to fight the Central Powers, and these ships were sitting ducks in the Atlantic Ocean. They needed a way to fend off the torpedoes.

Conventional high-similarity camouflage just doesn’t work in the open sea. Conditions like the color of the sky, cloud cover, and wave height change all the time, not to mention the fact that there’s no way to hide all the smoke left by the ships’ smokestacks.

The strategy of this high-difference, Dazzle camouflage was not about invisibility. It was about disruption. Confusion.

Torpedoes in the Great War could only be fired line-of-sight, so instead of firing at where they saw the ship was at that moment, torpedo gunners would have to chart out where the ship would be by the time the torpedo got there. They had to determine the target ship’s speed and direction with just a brief look through the periscope.

The torpedo gunner’s margin of error for hitting a ship was quite low. Dazzle painting could throw off an experienced submariner by as much as 55 degrees.

A journalist at the time referred to these dazzling ships as “a flock of sea-going Easter eggs.”

An American “Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps” did some of the painting.

Dazzle was occasionally ridiculed…

…but Dazzle also became an influence for fashion.

Our expert this week was Roy Behrens, a professor graphic design at the University of Northern Iowa. He’s published several books about camouflage, and also runs the Camoupedia blog.

The theater of war has changed so camouflage has changed with it, but there is still Dazzle to be found.

But sadly, there are no longer flocks of sea-going Easter eggs.

Built for Speed

I want you to conjure an image in your mind of the white stripes that divide the lanes of traffic going the same direction on a major highway. How long are the stripes and the spaces between them? You can spread your arms out to estimate if you want to.

Over the course of many years, a psychology researcher named Dennis Shaffer at Ohio State asked students from many different parts of the country this question and the most common response was that the white stripes are two feet long.

Tom Vanderbilt, author of the brilliant book Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says About Us), reveals the real answer and some of the other perceptual countermeasures that are designed to make you feel comfortable going way faster than your brain can adequately process.

We also talk about how the design language of exaggerated scale and wide vistas is great for limited access highways, but it’s problematic when these features are grafted onto suburban landscapes where they don’t belong.

Guerrilla Public Service

At some point in your life, you’ve probably encountered a problem in the built world where the fix was obvious to you. Maybe a door that opened the wrong way, or a poorly painted marker on the road. Mostly, when we see these things, we grumble on the inside, and then do nothing. But not Richard Ankrom.

In the early morning of August 5, 2001, artist Richard Ankrom and a group of friends assembled on the 4th Street bridge over the 110 freeway in Los Angeles. They had gathered to commit a crime — one Ankrom had plotted for years.

Twenty years earlier, Ankron, then living in Orange County, was driving north on the 110 freeway. As he passed through downtown Los Angeles, he was going to merge onto another freeway, the I-5 North. But he missed the exit and got lost. And for some reason, this stuck with him.

Years later, when Ankrom moved to downtown Los Angeles, he was driving on the same stretch of freeway where he’d gotten lost before. He looked up at the big green rectangular sign suspended above and realized why he missed the exit all those years ago.

The sign was not adequately marked.

The I-5 exit wasn’t indicated on the green overhead sign. It was clear to Ankrom that, the California Department of Transportation (known as Caltrans) had made a mistake.

Ankrom, an artist and sign painter, decided to make the Interstate 5 North shield himself. He also decided that he would take it upon himself to install it above the 110 freeway.

He would call it an act of “guerrilla public service.”

Ankrom started by studying L.A. Freeways signs and holding up pantone swatches to perfectly match the paint color. He dangled over bridges to measure the exact dimensions of other signs.

Most importantly, Ankrom consulted the MUTCD, The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which provides “uniform standards and specifications for all official traffic control devices in California.”

Ankrom wanted his sign to be built to the exact specifications of Caltrans, which were designed to be read by motorists traveling at high speeds.

He copied the height and thickness of existing interstate shields, copied their exact typeface, and even sprayed his sign with a thin glaze of overspray of gray house paint so that it wouldn’t look too new.

If he was successful, no one would know that the signs weren’t put up by Caltrans.

As a finishing touch, Ankrom signed his name on the back with a black marker, like a painter signing a canvas.

Then came the next phase of the project: the installation. Ankrom planned it with the precision of a bank heist. He cut his hair, bought some work clothes and a hardhat and an orange vest. He even made a Caltrans contractor-esque decal for his pick-up truck.

He feared he could get arrested, or worse — drop the sign or one of his tools on the cars driving underneath. But he felt it was too late to turn back.

On August 5, 2001, Ankrom parked his truck and went to work. He positioned his ladder over the razor wire and made his way up to the catwalk under the sign, nearly 30 feet above the highway.

The whole installation took less than 30 minutes. As soon as the sign was up, Ankrom packed up his ladder, rushed back to his truck, and blended back into the city.

For about nine months, only a small group of people knew that the Interstate 5 shield hanging above the 110 freeway was a forgery. Then one of Ankrom’s friends leaked the story to a local paper. And that’s how Caltrans found out.

Ankrom had hoped he could get his sign back from Caltrans after they took it down; he figured he would hang it in an art gallery. But Caltrans didn’t take the sign down. His guerrilla sign had passed the Caltrans inspection.

More than eight years after Ankrom’s sign went up, he got a call from a friend who noticed some workers taking it down. His sign was being replaced as part of routine maintenance.

When the new sign went up, however, Caltrans had added the I-5 North shield not only to it, but also to two additional signs up the road.

There is another guerrilla public service project in New York City by a group called the Efficient Passenger Project. The EPP has been hanging signs in subway stations informing people where they should board the train to make the most efficient transfers.

Even though the EPP’s signage has the look and feel of those from the MTA, they are completely unaffiliated. The MTA considers these signs vandalism, and is taking down the signs as fast as they go up — they have also done the same with other guerrilla subway signage.

The point being, if you decide to undertake an act of “guerrilla public service,” just know that it may not be received as such, so proceed with caution and avoid getting caught.’